IFS sessions can feel psychedelic even when you’re not on anything. You close your eyes, go inside and stay open to what arises. Many sessions are lateral; lots of parts come up, and we track and name them together, making a map of your system. In the process, you feel yourself relax, as if there’s an internal sigh of relief. But sometimes you work really intensively with one, or in this case, two parts, witnessing them and then inviting them to let go of the crap they’ve been carrying for so long. When this happens, it feels monumental.

I am desperate for an IFS therapy session after my post-journey backlash, but it takes another week to get an appointment. When it comes, it is perfect timing.

I start by explaining my predicament to my therapist, Toni. After a psilocybin experience brimming with love and forgiveness, I’d woken up in a deep funk. I trace my bad feelings back to some of my earlier selves: two five-year-olds locked together in a never-ending torture scenario. Monster girl rips into the soft pink belly of victim girl, a Prometheus who rejuvenates every night so that she can be eviscerated anew the following day.

As I close my eyes and go inside, Toni helps me separate the girls and sort through the other voices that come up, a chorus of impatient skeptics singing, “Why bother? This will never work.”

“Thank them and ask them if they can give us some space,” she says.

I imagine these thin grey wraiths of hopelessness sitting together in a conference room. I turn victim girl over to their care. They seat her at the head of the table, give her art supplies and proceed to oo and ah at the drawings she makes. Safe from the monster girl, victim girl starts to look less like a pink translucent piggie and more like a real girl.

Now it’s just me and the monster girl in my murky childhood bedroom. She is seated on the floor by the bed, cheek resting on the fuzzy pink bedspread with the kelly green lining. She stares at me balefully, yet she too is starting to look more girl than monster. Soon she has pulled out drawings to show me. They are childlike, crude and violent, stick figures with their heads ripped off, spurting blood in angry slashes of cadmium red.

She also shows me memories. Like getting spanked for accidentally slamming the door to my room on the new puppy. I am furious about being sent to my room Again and I didn’t notice the puppy on my heels until she squealed in pain. My dad didn’t ask me what happened, he just grabbed me and started wailing on me. My mom was the one who wailed on me, not my dad. I’d thought of him as the safer of the two, my ally. That day I realized that the puppy mattered more than me. The girl showed me how I’d closed my heart to that dog and to all dogs until well into the next century, when the loneliness of Covid-19 and the insistent affections of a certain shepherd mutt force me to reconsider my position.

Next, I see my grandparents coming to visit. My grandfather is a minister, my grandmother a minister’s wife. My family doesn’t go to church, but that Sunday we do, to the big brick Southern First Baptist in the middle of downtown. We sit in white pews upholstered with yellow velveteen. The stained-glass Jesuses are in a pastel palette. When the minister asks, “Are there any visitors with us today?” I raise my hand and an usher immediately approaches.

From there my memory goes blank until we are at the house again and I am in my room finishing up a drawing I’ve made to welcome my grandparents. It shows them happily waving from the windows of their Oldsmobile station wagon. I go to the guest room to present them with this welcome gift, but they are packing. They don’t make eye contact with me. Then they leave even though they just got there. My mom looks like she’s been crying. “I told them that we don’t believe in God and we don’t go to church,” she says.

Older parts remind me that this is what my parents do when they visit me and I am displeasing: they change their plans and leave early. One time when they visit me when I’m in grad school in LA, my mom calls and says, “We’re leaving later today, so you better come see us now.” On my way to their hotel, I rip the side mirror off my Honda Fit when I pull out of my garage. It dangles from the door by one wire. I have to pull the car over on Venice Blvd because I’m sobbing. I call my AlAnon sponsor, who says, “if it’s hysterical, it’s historical.” At the time, I have only an inkling of what that history is.

I’m starting to space out. My therapist gently reminds me to get back to the room with the monster girl.

“Is she near you?” she asks.

I’m in a rocking chair and monster girl has crawled across the floor and grabbed ahold of my leg.

“That’s good, stay there.”

The girl is no longer a monster at all. Now the only monster is outside the door, raging, huffing, screaming. But the girl feels safe with me, she climbs into my lap. “Tell her she doesn’t have to be alone with this anymore, you’re here,” Toni says.

The girl in my lap tells me that it was here in this room that she decided not to have children. Her mother says to her, “whatever you do, don’t just be a housewife.” The girl takes that to mean don’t be a stay-at-home mom like her mom is that summer. “It’s boring,” the mother says, “playing with you.” Clearly, having to deal with children is a horrible thing.

“When you’re ready, I have a question.” Interest piqued, I open my eyes and peer at Toni’s face on the Zoom screen.

“If this burden she’s carrying were a pizza, how much of it is hers?”

“A fourth,” I say. A family size pepperoni in a cardboard box appears in the little girl’s bedroom.

“If she wants to release that three-fourths to one of the elements, how would she do it?”

Monster girl is already on her feet wielding a flame-thrower, incinerating the pizza box where it sits on the floor by the window. Not only is the pizza completely torched, but the curtains go up in flames, the window shatters and soon all that’s’ left is a smoldering hole in the wall that leads to the front yard.

“She’s just opened up a lot of space, what does she want to take in?” Toni asks.

“Confidence,” comes the answer.

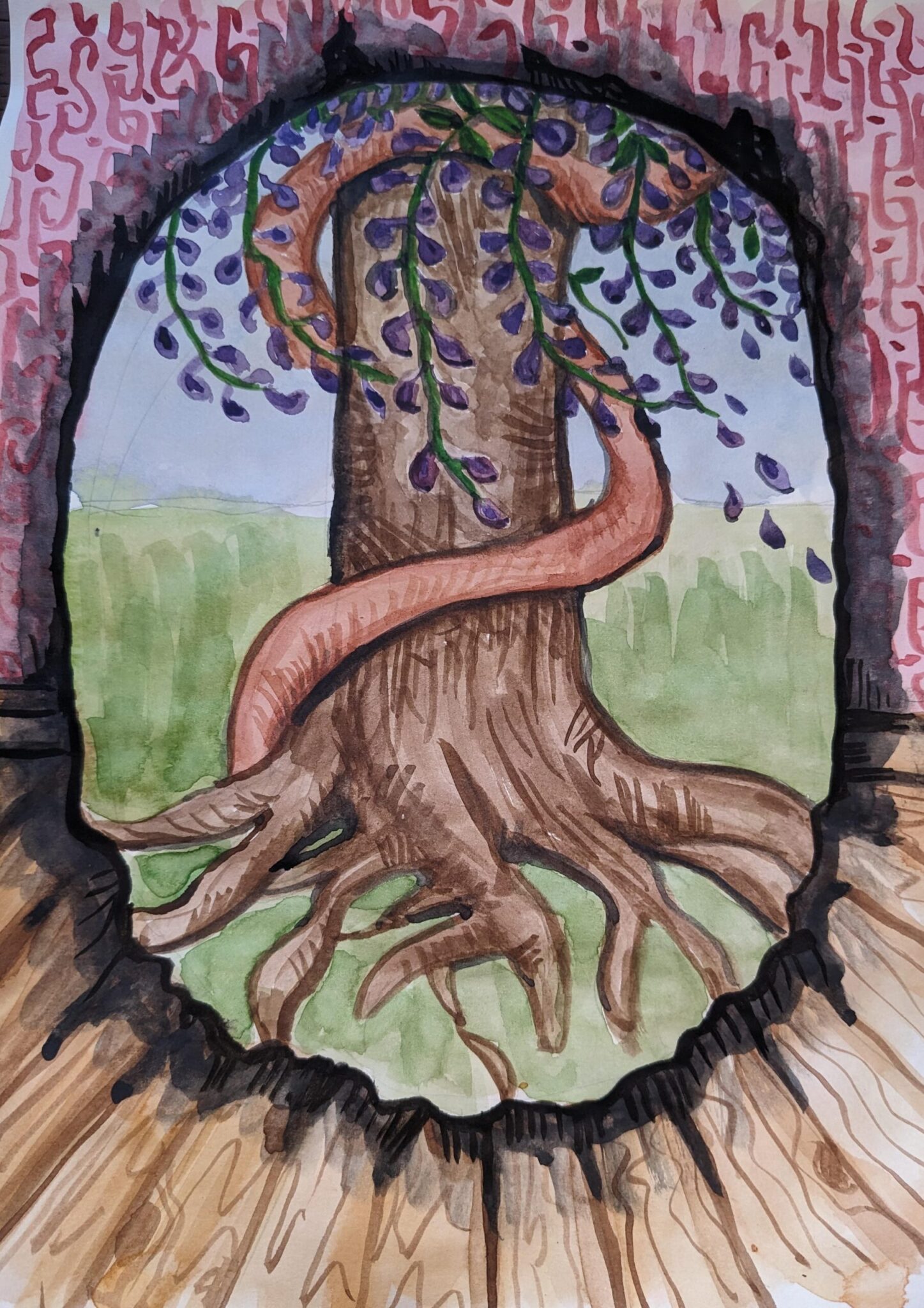

The girl and I step through the gaping hole in the wall. Out front there’s a towering conifer wrapped with a wisteria vine, its delicate purple flowers hanging like airy bunches of grapes. We put the remaining pizza slices in a shoe box as if they were a dead hamster. I dig a deep hole between the roots of the tree.

Once we’ve patted the dirt down and taken a moment of silence, it’s time to invite victim girl back to the scene.

She doesn’t know what’s happened because she’s been busy drawing. She’s alarmed by the destruction to the room. “What will mommy say?”

“Don’t worry about mommy, we don’t have to live here anymore,” I tell her.

But first we need to do this process with her. She makes tissues full of sadness, until there is a sodden mass piled up on the couch beside me. When she’s done crying, Toni asks her the pizza question too.

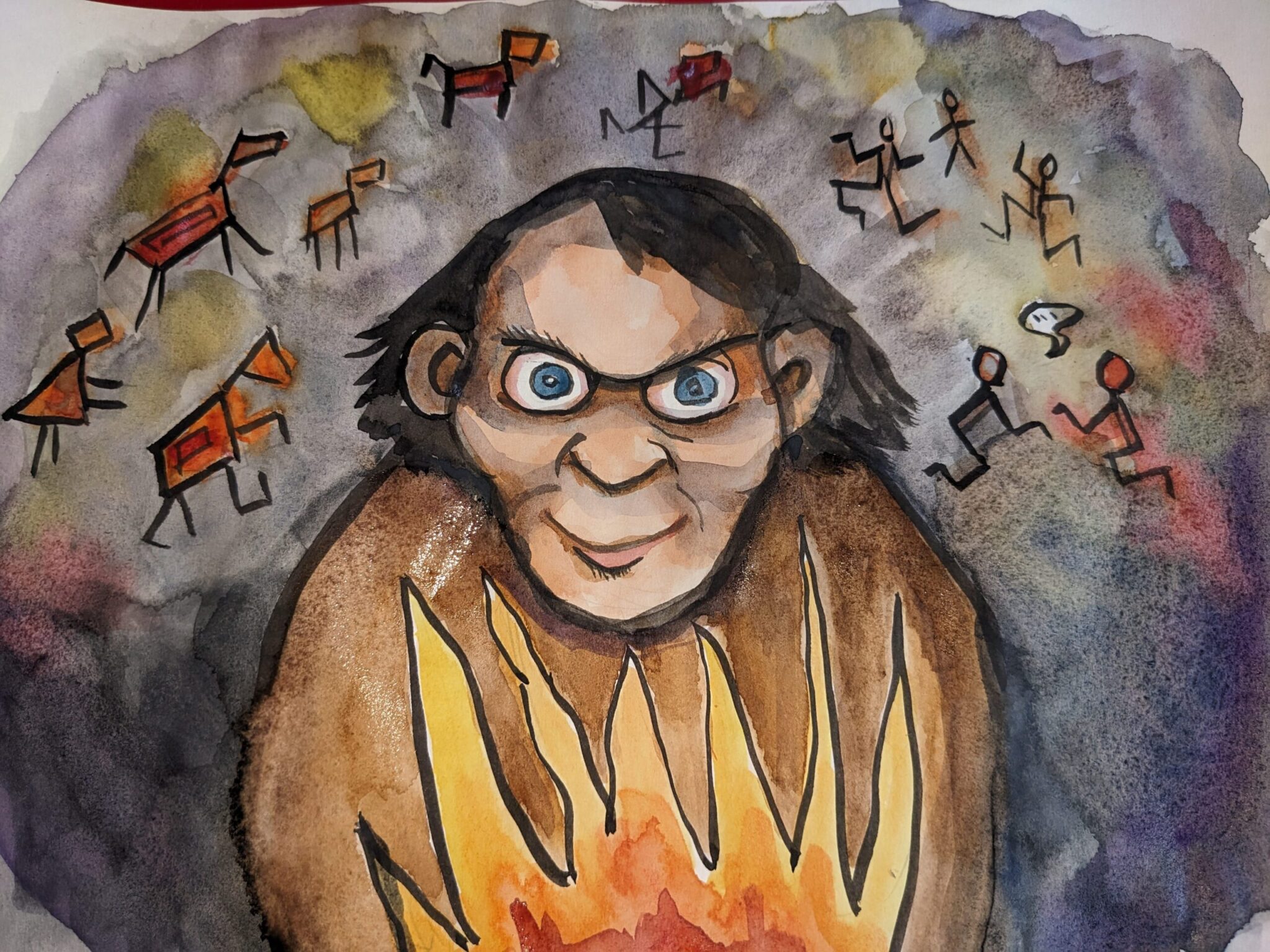

She gives the same answer: three fourths is not mine. This time we pass back this bundle of pizza through the generations, both maternal then paternal, back to an originary ancestor, a woman alone in a cave, who burns it up in a fire.

(A little voice niggles at the corner of consciousness: isn’t pizza an anachronism for a cave person?

Another replies: just go with it.)

Then she to is asked what she wants to take in. The answer is equanimity. Calm. Two things women in her mother’s family never had.

“Good, hand that back along the lineage until it gets to you.”

Then I imagine doing the same with my paternal lineage, going back until I see a man alone in a cave with a fire, burning his sacred bundle of pizza. The flames leap up, revealing the delight in his face and the drawings covering wall behind him, figures painted with charcoal, blood and pee. “Creativity,” is the answer to the question about what quality he wants to take in. He passes this quality back through the lineage to us.

The victim girl also wants to bury her remaining pizza slices. They too are placed in a deep hole under the tree. Then we stand there solemnly over the tamped down dirt.

“Now that there’s this space opened up within her, what does she want to take in?”

“Clarity,” she says. The victim girl sees clearly that this shame wasn’t hers. Just because her parents can’t love her for who she is doesn’t mean that she’s unlovable.

Toni suggests that we invite back in the other parts who came up today. The grey wraiths with long drawn faces file in from the conference room. They look surprised. And remain skeptical. “Will this really work?”

“I love those skeptical parts,” Toni says. “They keep us honest.”

Then she has another question: “Ask the girls if they want to stay here or if there’s somewhere else they want to be.”

Instantly the girls are transported to a tea party on a picnic blanket in a meadow. The skinny orange tabby is there too. Unlike real life, this cat will not alternate aloofness with hostility before getting poisoned by the neighbors. The cocker spaniel puppy is at the picnic too. This dog won’t be beaten bloody with a rolled-up newspaper during bath time while the mother screams NO NO NO NO with each whack. No, the girls will raise these animals gently and they will stay sweet and loving and affectionate, just like the girls are now.

“Is there anything else needed to make this complete? “

“Just a promise to check in with them,” I say.

When I do later that day, the girls are starting to look more alike, cute and chubby like Campbell soup kids, quaint like Henry Darger’s Vivian Girls. They are in a bed in a cabin near the field, taking a nap together, their pets piled up on them.

I text my boyfriend and I tell him the little girls are getting along now. Muy bien, he says, ya te sientes mas tranquila. I do feel more tranquil, for the first time since my psychedelic experience eight days earlier.

I also feel exhausted, but I shower and put on a dress and walk to meet him at an art opening in Centro with my dog Panda. She’s the first dog I’ve ever loved and taken care of. I bring her because I’m feeling sentimental and want to spend time with her, even though I’m a little worried about the appropriateness of taking a dog to an art opening. Plus Panda has her own victim/monster dyad going on: sometimes she is submissive and sweet and sometimes she is vicious and snarly. But when we get there, Panda is lovey, rolling at the feet of her admirers, proffering her belly for rubbing.

After the show, I find myself with an overwhelming desire to eat pizza, and it takes me a minute to remember why. My boyfriend and I go to the pulqueria near my house and order one with pepperoni. We eat three fourths of it.

That night I sleep curled around his long back. Panda snores at the foot of the bed. As I drift off to sleep, I think about my five years olds slumbering in the cabin off the meadow, spooning each other under a quilt, the puppy pressed to one girls’ belly while the kitten nestles in the curls of the other girl’s hair.