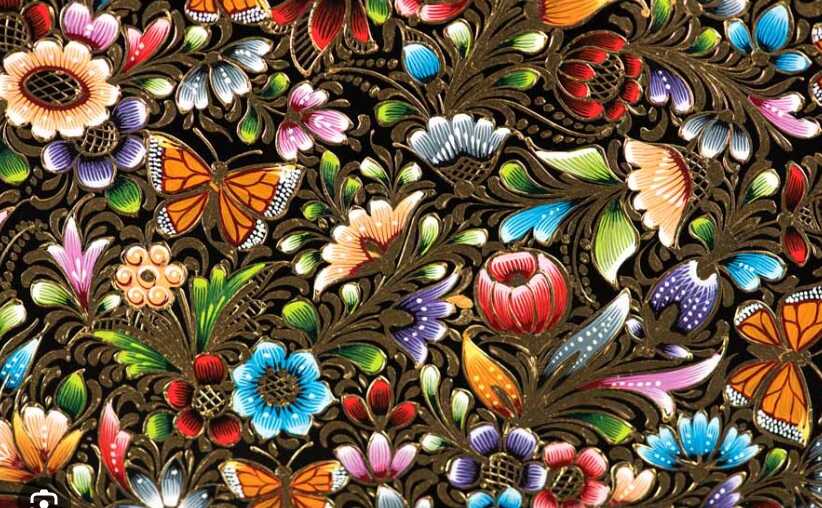

The attachment was blurry, a small circle counting down in its center. I was alone at the casita I’d rented in the country just outside of San Miguel de Allende, on the phone with my boyfriend Jared. We were struggling to revise a house concert flyer over spotty signal. At last, the image popped into view, a colorful floral design splashed across its top. As I recognized the pattern as one typical of the lacquerware made in Patzcuaro, Michoacan, my mood darkened. “Naw,” I heard myself say in a tone bordering on the grumpy, “too busy. It makes the text hard to read.”

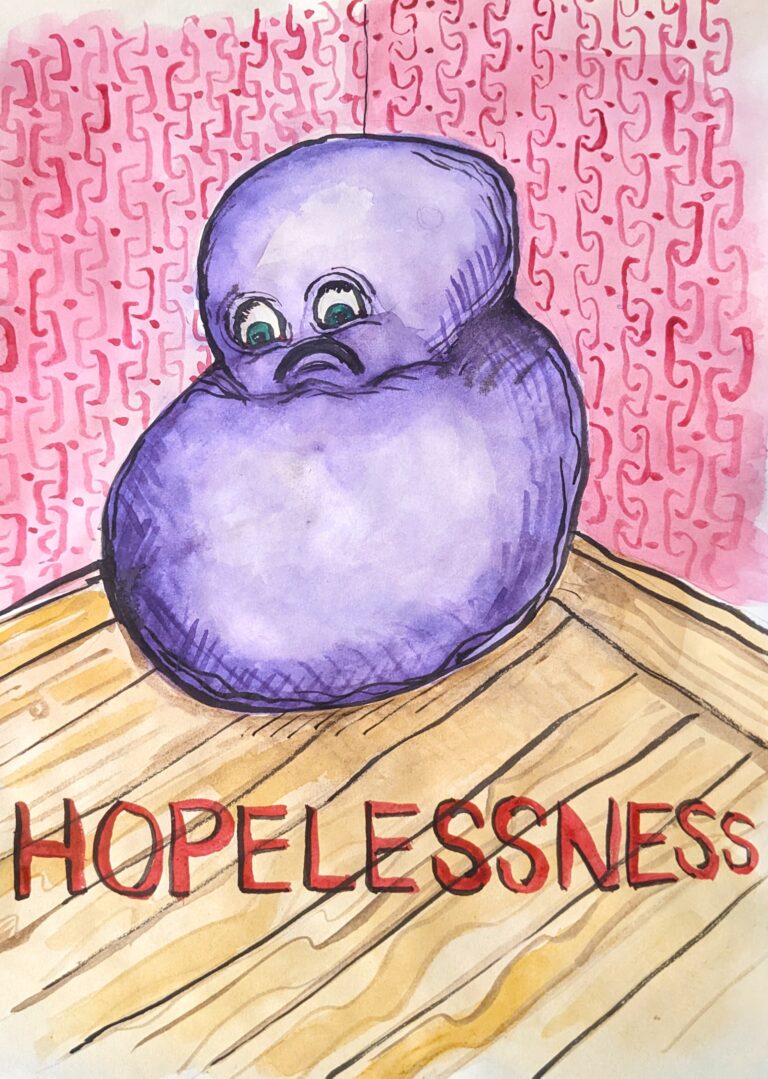

That night I lay down in the unfamiliar bed feeling unsettled. I stayed awake for hours, unnerved by the clanging of wind chimes, unrecognizable bird calls, and the scurry of mice in the next room. Something about seeing those flowers had set me off. Finally, I gave up, got up and started writing. It’s what I do when I can’t figure out why I’m feeling what I’m feeling.

There was work that needed to be done; namely, a write-up of our interview with Kúperakua, the Purépecha musicians playing at our May 24 house concert. The piece I’d written about the first concert, music from the adjacent region, Tierra Caliente, had flowed easily. But I felt stuck when it came to describing la música de Tierra Fria. Instead of working on that article, I found myself writing about Patzcuaro, a town central to this region.

I’ve loved Patzcuaro ever since I first visited it with my then boyfriend Angel in 2012. It boasts two central squares, small-town manageability, and a pleasing white and vermilion-accented architectural uniformity. The shops teem with beautiful crafts from surrounding Purépecha villages. I coveted the whimsical ones, ceramics of devils driving school buses, floor lamps made of reeds called chuspeta woven into the shapes of monkeys and macaws. And I admired the gourds, trays and boxes lacquered with the pattern I’d seen earlier on my cellphone screen, which came from an indigenous tradition of inlay adapted to European tastes.

I also loved the café on the corner of the main plaza, where I always bought fat colorful candles, chocolate-covered espresso beans and kilos of dark roasted coffee from Uruapan. One day while eating a late breakfast with Angel, an older gentleman strolled by and started serenading us with pirekuas, folk songs of love and longing. He sang in a clear high voice in Purépecha while gently strumming a guitar. Purépecha, an isolated tongue unrelated to any other, is still spoken around the Lake Patzcuaro region. During our interview with the band Kúperakua, guitarist and singer Erik Cruz asserted that these songs need no translation: “Pirekuas are simple structures laden with feeling. When we sing, the meaning gets transmitted directly to your heart, so you can get what we’re saying without understanding the words.”

Cruz’s words were certainly true for the me of 13 years ago. I found these tunes so beguiling that I bought the busker’s CD. The package and the disc inside were both decorated with a flowery pattern taken from a lacquerware design. On the four-hour ride to where we lived just across the eastern border of Michoacan, I played it over and over again, so I could stay in this feeling of contentment, in the novelty of new love. At last Angel said, “change the music, you’re going to put me to sleep.”

As the insomniac me of the future reconstructed these details, I noticed that they’re mostly about things, not so much about Angel. Of course, it had started off romantic. Angel and I met in a storm of monarch butterflies; he was the guide who’d taken me to their colony. Now I wonder if the appeal was more about what the relationship allowed me to do than the relationship itself. We created an ecotourism business in his isolated village at the entry of the least visited monarch butterfly sanctuary, growing it from four rooms to fourteen.

Because there was nothing to do in Angel’s hometown, I threw myself into curating experiences for our guests. Our butterfly tours began with my orientation on monarch biology, history and conservation, because I knew that understanding the context increased my paisanos enjoyment of the experience. I organized cottage industry tours of the village and sunset concerts on my back lawn, contracting the all-strings trio that otherwise only played wakes and funerals. I created events where visitors and villagers came together in what felt like a perfect meld, more than the sum of its parts. I loved that part of my life. Yet the more my projects succeeded, the more fraught my partnership with Angel became.

For a long time, I held onto hope just like I held onto that floral-printed CD, tucked away in the side pocket of the car, pulling it out to listen to pirekuas whenever I drove to our nearest city for supplies. Hearing that mysterious tongue full of clacky consonants and mushy vowels reminded me of when my relationship felt new and full of possibility.

One day, Angel hired a down-on-his-luck cousin to wash the car. Angel sat in a lawn chair drinking a beer and supervising while Pepe lathered and rinsed the black Jetta. Pepe kept smiling his big gummy grin while my now husband teased him mercilessly about not having a girlfriend. Eventually Pepe was given his own beer. I’d started to realize that Angel didn’t really have friends: he had employees.

The next time we drove to town, when I reached into the side pocket of the passenger door for a CD, my hand grazed its freshly scrubbed bottom.

“Where are my CDs?”

“I don’t know, I guess Pepe threw them out.”

“Threw them out?”

“Yeah whatever, you never listened to them anyway.”

I tried to keep my voice even as I said, “I did listen to them.”

Angel kept his eyes on the road. “It was just garbage that you left there.”

“What about the CD of pirekuas I bought in Patzcuaro?”

“They put me to sleep,” he shrugged.

At times I got so furious during car rides that I would open the door and threaten to jump out. Other times, I screamed so loudly that Angel looked scared. “You’re going to make me have an accident!” But rageful reactions to his provocative behavior made me feel like the crazy one. I ended up having to apologize while he never apologized for anything. Ever. So I shut down and went silent, watching the pines flash by outside the car window. He’d thrown out the CD that reminded me of when I loved him. He’d shown me, once again, that he was incapable of love. There was so much about my life that I did love that it took me several more years to organize my departure.

Now it’s been three and a half years since I left Angel and started over in San Miguel de Allende. I’d felt so betrayed that I swore I would never collaborate with a romantic partner ever again. And yet, here I am, collaborating on Conciertos Casa Elena with my new boyfriend, musician Jared Jimenez. So far, we’ve staged four musical events in the backyard of my San Miguel home. When we started out, a part of me was screeching, what the hell are you doing? And yet collaborating to bring something we love to others has only increased my appreciation of Jared, who combines quiet enthusiasm with thoughtful thoroughness.

Waking up in the morning after the Tierra Caliente concert, I still felt high on its success. Everyone had seemed so happy: the band, ecstatic, the audience, delighted, Jared, beaming all night. Lying in bed talking to him about it, I startled myself by bursting into tears. Once again, just like they would a few days later when I saw the lacquerware pattern, my emotions raced way ahead of my ability to apprehend them.

While Angel used to roll his eyes and say, “nobody died,” whenever I cried, Jared just hugged me and held the space. As my tears matted his chest hair, it occurred to me that I’d regained access to a particular kind of pleasure that comes from creating wonderful experiences. Somehow, I hadn’t been able to acknowledge how much I missed that part of my life until I’d gotten some semblance of it back.

In the casita in the country, I saved my document of 3 AM ramblings. I hadn’t realized how upset a part of me still was over the loss of my pirekua CD. Now that that part had spoken her piece, she felt softer. Outside, the wind and the birds had fallen silent. Inside, the mice kept to themselves. As I lay back down in bed, I felt an urge to listen to the music I’d been avoiding for years. I opened up a playlist of pirekuas Jared had sent me and hit play. A duet of ancient-sounding men harmonized in whispery falsettos, compressing then elongating the syllables of the song. “How pretty,” I thought just before slipping away into sleep.

❦

Kúperakua plays Purépecha music, including pirekuas, at Conciertos Casa Elena on Saturday, May 24, 2025 at 6 PM.

Jadhex Sonidos Prehispanicos will play on Saturday, June 21, 2025 at 6 PM. Read more about that project here.

Conjunto La Endiablada opened this concert series of traditional music of Michoacan on April 26, 2025. You can read more about the challenges facing that genre here as well as my personal essay on why this music is so meaningful to me.

Join the Conciertos Casa Elena facebook group here to see the latest in updates and videos.