There are many ways to access the Higher Self, the sacred presence within that’s the agent of all healing in IFS. The people of Paracho, Michoacán, have turned one of them into an annual ritual.

Collective effervescence, a concept coined by sociologist Emile Durkheim, refers to a collective ritual action that makes an individual feel like part of a unified whole. While I’ve explained this idea to undergraduate anthro majors, I wasn’t sure I’d ever really experienced it. Collective effervescence was something for stadiums full of sports fanatics, not for me.

Then I spent a weekend in Paracho, Michoacán.

Apart from the guitar festival this town hosts every August, different trades have a day dedicated to parading from one side of town to the other. Everyone is welcome to join these processions. Bakers, butchers, and market vendors fall earlier in the week, while Paracho’s most exalted profession, luthiers (guitar makers) celebrate themselves on the last day of the festival.

When I met up with my boyfriend in Paracho, people made conversation by asking us, “Are you going to parade?” In Spanish ¿Van a desfilar? sounds much more natural. Alternately they’d inquire, “Are you going to dance?” ¿Van a bailar?

As is my wont, I started feeling some anxiety about this mysterious thing we’d committed to doing. Would I know how to do it right? “What’s the dance step?” I asked my beau.

“You’ll see, it’s not hard,” he replied.

“What do we do with this whole bottle of tequila?”

“You’ll see.”

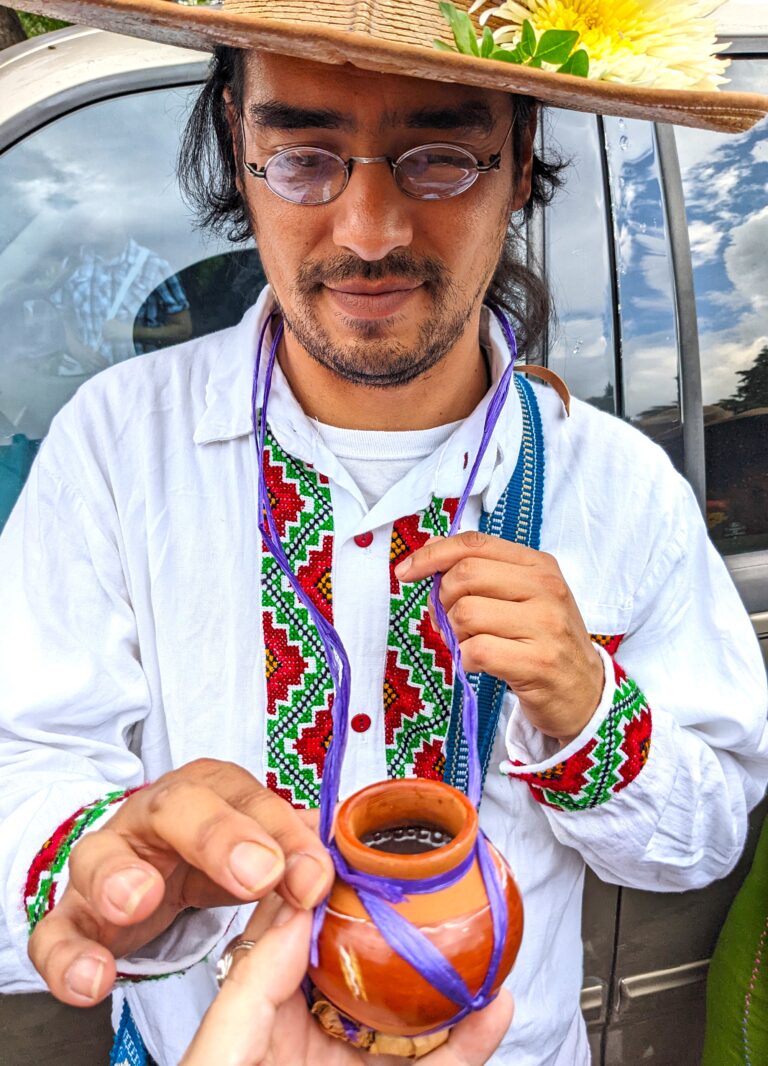

We went about preparations, buying wide brimmed straw hats typical of the region before handing them off to the florist to have them adorned with flowers. We bought small mugs attached to ribbons that hung around our necks. I bought an embroidered blouse and a colorful shawl and a bag woven from fiber of maguey.

At noon, we traversed blocks filled with floats and banners and at least a dozen uniformed marching bands until we found our contingent. People perambulated, pouring tequila or mezcal liqueurs into our tiny cups. Storm clouds gathered overhead.

Suddenly the crowd in front of us surged, and we were off, walking in between the banner identifying our group and the brass band. We linked arms forming rows the width of the street, and proceeded, trotting three steps forward and then two steps back. We only broke arms to accept more shots of tequila.

I was glad for the morral that looped around my shoulder and the hands-free cup dangling from my neck, because sometimes our whole row took off running in what felt like a manic ring-around-the-rosey. Our line wove its way up the side of the street before dashing between other rows of revelers and returning to our spot. Inevitably someone else arrived to fill our cups, while we gave our tequila away to others.

Sidewalks packed with people cheering us on lined the parade route. Lines of children joined arms and snaked their way through our rows while laughing gleefully. People in our group who had toy guitars strung around their necks start giving them away to spectators.

Drizzle turned to downpour. The band, made up of guys with shiny metallic blazers and coiffed hair, continued its blare, the tuba keeping time. Rain saturated my straw hat, releasing the smell of wet hay. Rivulets dripped down my forehead, collecting on the tip of my nose. Glasses steamed up and women in traditional Purépecha garb hurriedly handed their cellphones to men blessed with pockets. Now our dance step took us splashing through puddles, galloping forward and then leaping back to avoid the retreat of the row in front of us.

I couldn’t film any of this because I was too busy keeping my neighbors’ arms from slipping out of mine, as we kept pace with the wave of undulating rows before and behind us. I felt myself entering a trance state, one where I’m fully and completely present, really and truly happy, connected to everyone and everything, drunk but not like any kind of drunk I’ve been before. “No te suben,” my boyfriend remarked about this kind of active, ritualized drinking. Or, the alcohol doesn’t affect you the same way.

Unlike fiesta season where I used to live, 190 miles east of here, I didn’t sense any undercurrent of danger. It can get a little scary when people raised to repress all negative emotions get wasted and drop their inhibitions. But in Paracho, we were all good drunks, smiling and laughing, even when we wiped out in puddles, even when the sky pelted our parade with hail. In the middle of this soggy bliss, I heard a little voice in my head saying, “So this is what Durkheim was talking about.”

Much like a psychedelic experience, the afterglow stayed with me, through the peeling off layers of sodden clothing and basking in a hot shower, into the comfort of dry clothes. Then came the hub bub of the after party, where we ate the most incredibly delicious stew with fall of the bone tender beef sopped up with corundas made with just the right amount of manteca.

When the bands started playing, I realized that other people in our rows are secretly super-talented musicians dedicated to revitalizing the music of the pueblos originarios of the region. There are pirekuas sung in Purépecha and sones from Tierra Caliente. In a day where everything feels superlative, it feels like the best music I’ve ever heard in my life.

The next day I totally crashed. I tried to comfort myself by intellectualizing it, thinking about how awesome it was that I’d experienced a new way of accessing my Higher Self, the inner presence that’s essential to all healing in IFS. But thoughts don’t help much after burning through so much serotonin all at once. I felt slow and deflated as we boarded the Paracho-Uruapan bus.

On the ride, my boyfriend explained to me that at end of the night I’d inadvertently violated some unspoken social norms when I insisted on leaving before the last pirekua was played. This information triggered a very young part within me, the one shamed about social interactions, and I started sniffling. Then another part jumped in to shame the shamed part about having a public meltdown so early on in a tender new relationship.

“It’s okay,” he said, patting my knee. “Now you know for next year.”