Saturday night found me at home in my jammies nose-deep in a book about shame. Though the scene (herbal tea, fuzzy blanket, snoring dog) was placid, my inner landscape was in a tumult. I’d just had a thing cut out of my foot and I wasn’t supposed to walk. I’d recently ended a friendship and felt sad about it. And a few weeks earlier, I’d made the decision to give up booze forever. All of that may sound like a recipe for self-pity, but instead, as I scribbled notes from Martha Sweezy’s Internal Family Systems Therapy for Shame and Guilt, I started feeling something closer to ebullience. The last two facts, lost a friend, quit drinking, on the surface unrelated, started to reveal hidden connections.

I’ve complained elsewhere about the refusal of IFS to explicitly address narcissism. That evening, I realized it did, right there, in Sweezy’s breakdown of the dynamics of shame. After all, narcissistic traits are typically explained in terms of shame intolerance. In the origin story, sufferers are shamed out of their authentic selves as little ones. In the stead of authenticity, they construct a series of false selves that range from the grandiose to the vulnerable. And when their exiled shame gets activated, watch out: they ease their discomfort by projecting their disowned, despised qualities onto you.

The genius of Sweezy’s discussion of shame is her insistence on its relationality. There is always a shamer, someone doing the shaming, and a shamee, a person with parts primed to receive shamefulness. Often this interaction happens internally between parts of our own system. When this private process cannot be contained, it spews out into the world in barbed comments and blaming.

Sweezy explains shame in terms of, “a multi-act cycle occurring in the plural mind.” Plural mind refers to the premise of Internal Family Systems (IFS), which sees the psyche as a collection of multiple sub-personalities, AKA “parts.” The first two acts of the shame cycle are necessarily sequential, while the remaining four overlay and repeat. The curtain opens with an event, or, more likely, an accumulation of invalidating, soul-destroying events, many preverbal and blurrily remembered at best.

Act 1:

A child is shamed.

Act 2:

The child accepts the shaming as valid information about who they are.

No one escapes the vulnerability of childhood without some bad experiences that end up transmuted into shame. It’s the way little ones make sense of the world; something bad happened to me turns into therefore I must be bad. I once heard Gabor Maté say that just breaking eye contact with a baby is enough to create shame. Sweezy too offers a capacious definition: “Invalidation is shaming. Any behavior that says, I don’t see you, you don’t matter, or I will use you is shaming.”

Act 3:

Protective parts arise to shame the part who was shamed. Here’s where we get our inner critics, judges, and evaluators. This brutal inner diatribe seeks to keep you safe by criticizing you before someone else can.

Act 4:

An additional layer of protective parts form. Like the players in Act 3, they too share the goal of keeping us safe, just with more of an outer focus. Sweezy calls them, “our fearful scouts anticipating danger.” These parts police our way of being in the world, ever on the alert to avoid doing something that could evoke shaming. I imagine them saying, keep your head down, stay small, it’s not safe to shine. Or my grandmother’s favorite, don’t get too big for your britches.

For the narcissistically injured, the shame show mostly stays on this level, a low hum of fear and discontent, almost out of ear shot. But on a bad day, narcissistic parts take the wheel in a misguided attempt to banish emotional pain. Which brings us to…

Act 5:

Protective parts jump into action to distract from inner shaming by tossing the “hot potato” of shame to someone else. As Sweezy describes this, “Some reactive firefighter parts shame other people, diminishing them by comparison and rebooting the self-esteem of a system that is collapsing under the weight of internal shaming.”

Instead of labeling people narcissistic, viewing this pattern of behavior as a relational process arrayed on a spectrum offers much more nuance. After all, all of us have parts in our system that lash out sometimes, cussing at the driver who cuts you off, judging what someone was wearing, criticizing something your partner did or didn’t do.

The distinction for me is that people lower on this narcissistic spectrum are capable of catching themselves, recognizing the rupture and making a repair when needed. People on the high end tend to be incapable of this level of self-examination. If you say to them, what happened hurt my feelings, they respond, you saying you feel hurt is hurtful.

Act 6:

Where there’s shame, there’s addiction. These can range from the usual suspect substances like drugs and alcohol to process addictions like workaholism, phone scrolling or Netflix binging. All of these processes are trying to relieve the suffering of the shame cycle. I’m reminded of the saying, not all narcissists are alcoholics, but all alcoholics are narcissists. True or not, I do imagine that there’s a sizeable Venn diagram overlap between these two groups seeking to numb out the unbearable pain of being them.

As Sweezy sums it up, “When we shame ourselves, we make a bad experience into a painfully false identity. When we shame others, we spread unease, pollute our relational environment and give the shame cycle immortality.”

These last words gave me chills as I sat snuggled up in my reading nook last Saturday. I pondered the passing down of this unexamined burden of shame from one generation to the next in my family. I thought too about the larger reverberations of the shame cycle in the ugly implosion of American empire going down all around right now. Because that subject makes me feel utterly overwhelmed and helpless, I pulled my thoughts back closer to home: Lost a friend. Quit drinking. Skipping Act 6, self-medication with that most available, most socially acceptable of substances, was allowing me to be much more present to my feelings around this recent loss.

You’ve read this far with the promise of a story, but in the interest of not polluting my relational environment any further, I’ll keep it as spare as possible: A friend of a friend sent some unsolicited advice my way. I experienced it as a hot potato. When I brought up my irritation with our mutual friend, she objected: You shouldn’t feel offended, it came from a place of love. When I maintained that I felt hurt nonetheless, my friend told me that I was being hurtful. These words landed like yet another hot potato. Reading Sweezy helped me understand why: “Invalidation is shaming.”

As I reflect on this energetic exchange, I realize I’ve skipped a step—the one where my friend felt implicated by my complaint about her friend’s comment. “We give each other unsolicited advice all the time,” she’d said defensively. I can only assume that my remark set off a shame spiral within her that she then discharged by denying my right to my reaction. That brings the tally to a total of four hot potatoes, starting with my initial share of something I’d made that I’d said I was “proud” of (see, you were asking for it, my Act 4 inner critics pop in to say). Sweezy makes another important point about shaming, which is this: our intentions are beside the point. Shame is in the eye of the beholder.

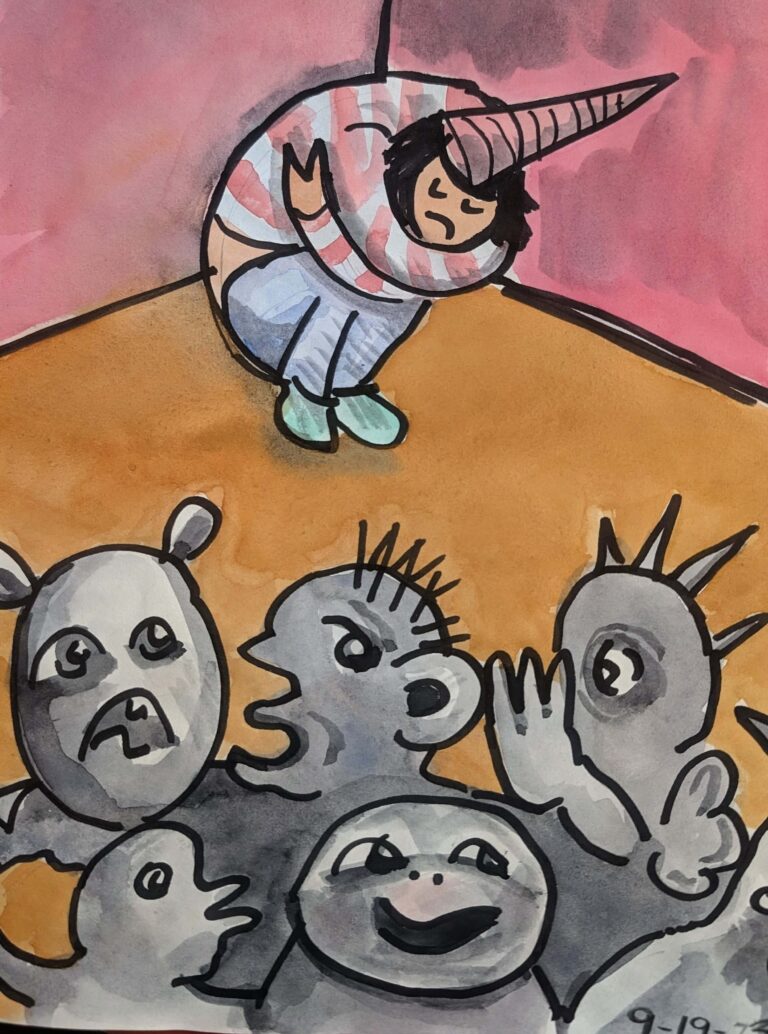

Looking into why being told I shouldn’t feel how I’m feeling felt so calamitous to me took me back to a late summer’s day in the 1970s. I was seven and feeling devastated that my only friend had just rejected me. “I don’t want to play with girls anymore,” he’d said, turning his back on me to resume a dinosaur game with my male replacement. And here my mom had thought it would be a good idea to drop by for an unannounced playdate. Boy was she wrong. I was so upset. As it usually did, my distress sent my mother into her own shame cycle. When we got home, rather than comforting me, she spanked me and sent me to my room. I was only allowed to come out once I’d squashed my feelings.

When I time-traveled back to this space in my psyche, I found a floral pink room packed with unhappy little kids, all of the selves I’d splintered into during these habitual “time outs.” Next to my exiled shame, I encountered a mean little girl who’d bullied her friend until he’d refused to play with her anymore. Acknowledging that I was a shamed kid who’d shamed others set off a shame spike in my system. I had to welcome and unburden my inner bully along with others hovering nearby who really didn’t like that one.

Revisiting this memory brought up other moments from other eras, making me painfully aware of how many times I’ve played all of the parts in this drama, papering over the pain with a range of addictive processes. Again, Sweezy’s schema has nudged me towards a spectrum view of narcissism, one that starts with the narcissistically injured (Acts 1-4) before boiling over into the narcissistically injurious (Act 5). I’m starting to think that instead of talking about narcissism, we should just ask where we’re at in the shame cycle when things go south between us.

Abstaining from Act 6 helped me to see this process more clearly. Not that those escape artist urges didn’t drop by all day Saturday, bearing messages like, wouldn’t a glass of wine at dinner be nice? I had to spend some time letting these parts know that we weren’t an awkward, anxious high schooler anymore, the one who needed to get schnockered on peach schnapps to bear being in the world. Now I have my Higher Self on board, and She says, dousing the shame with drink only ever leads to more shame.

Finally, eyes blurring, hand cramping, my reading binge wound down. I glanced at the last words I’d scrawled on my legal pad:

“Recovering from the shame cycle means shifting our core belief I am bad, to bad things happened to me, but I am not bad. It means having compassion for ourselves, feeling loved, and rejecting the message of shaming.”

I gazed around my space, the landing in the heart of my house where I’ve recreated my little girl bedroom, with just as many shades of pink but no doors this time around. I can no longer be shut away. As I took a sip of cold tumeric tea and leaned down to rub the soft shepherd dozing beside me, a voice rose up in the quiet:

We’re doing things differently now. The shame cycle ends with me.