I don’t want to admit what I’m about to admit. Here goes: although I claim expertise in the shepherding of psilocybin journeys, my last shroom experience laid me low for days. Like lying in bed sobbing in the middle of the day low.

Keep it to yourself, my PR part says.

But then there’s another voice: This is all part of your process. You’ve been shown where your work is. Maybe your honesty will help someone else.

That part won.

After my crash, I searched the internet for help. I got research write ups on how psilocybin cures depression (but nothing about what to do if it causes it) and other articles about what to do after a bad trip.

But far from a bad trip, I’d had a fantastic voyage. On Wednesday afternoon I was thrumming with pleasure on the day bed on my sun porch, peering up through the branches of the backyard mesquite and into the great blue beyond. The walls of my back patio framed an incredible ever-changing sky show. The clouds morphed libidinally, showing me a pulsating anus followed by long-snouted doggies snogging replaced with monkeys engaged in erotic lactation.

When I took a break from this entertainment, I cradled my foot and had a meaningful conversation with an aching bunion. I inquired into the source of its woe. “Let go of your anger,” it said. “It’s only hurting you. Forgive everyone and everything.”

I felt flooded with hopefulness, good will, optimism. I reviewed stories I’d heard myself tell recently, this time hearing places where I was holding resentment, and I made a decision to let it go. All of it. Oh forgiveness, beautiful forgiveness!

So far from a bad trip, it seemed like the best of all possible trips, profane and sacred and bursting with love.

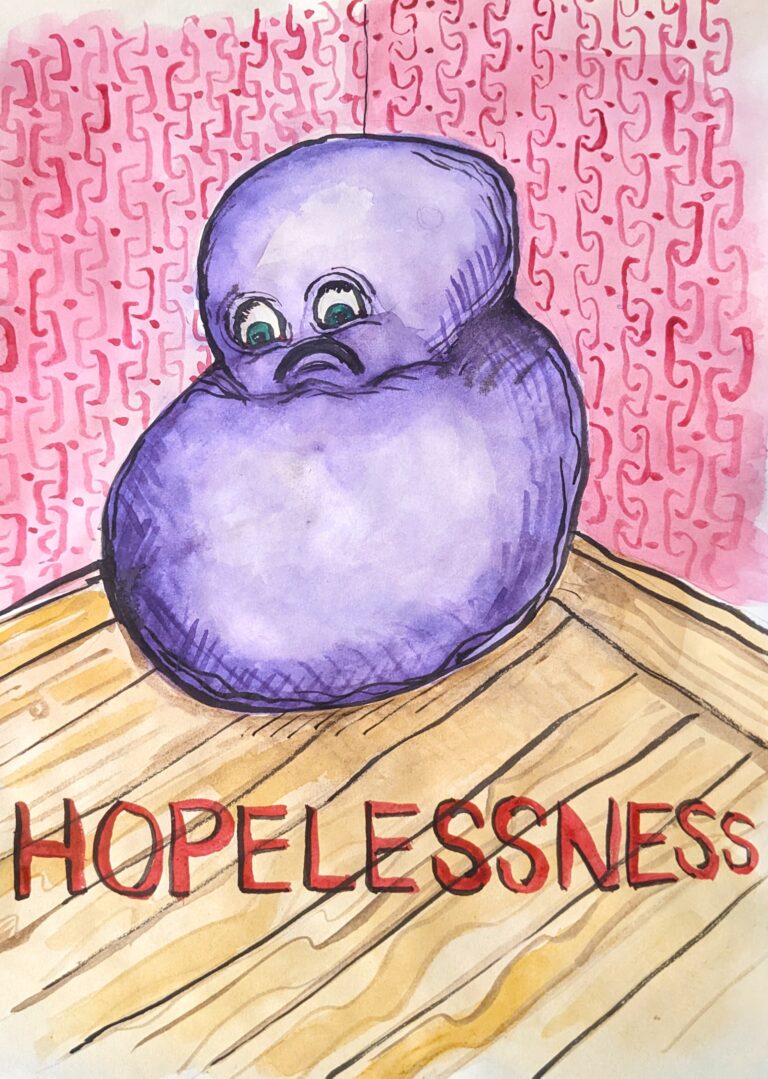

In the past I have suffered from post-shroom hangovers, a sudden gloominess bursting the bubble of a rosy 24-hour-long afterglow. But I’d always been able to remind myself, “you’re just chemically depleted.” Just the act of acknowledging it made me feel better.

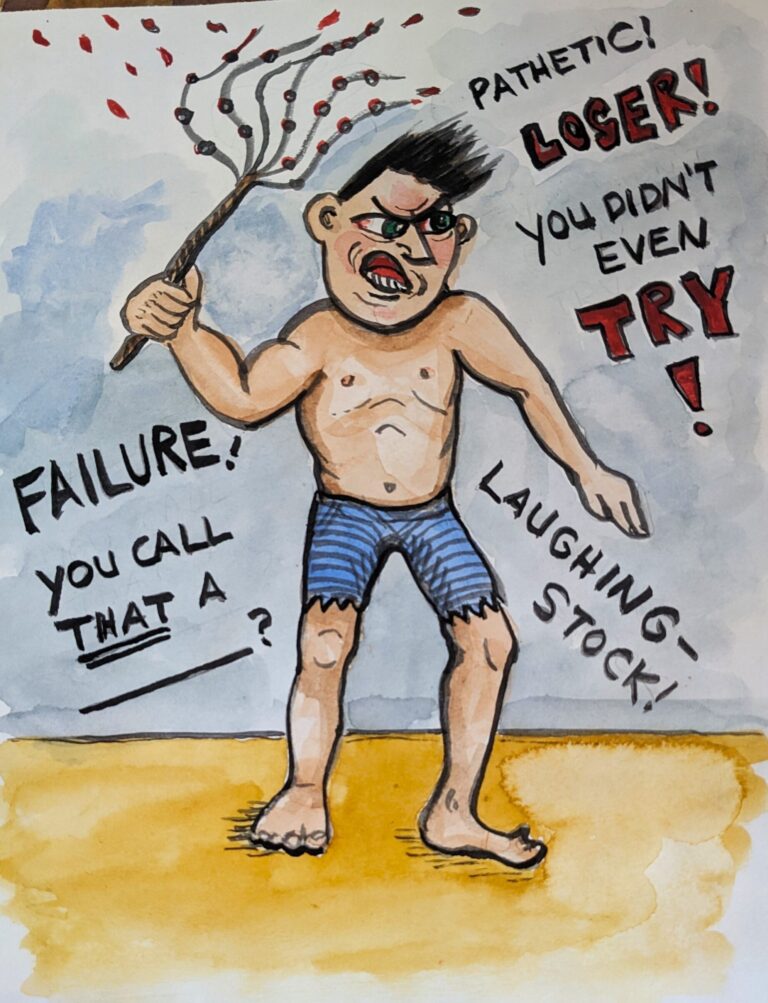

Not this time. Thursday, Friday, well into Saturday, I was besieged by the meanest, most lacerating of inner critics: things are not okay, they have never been okay, they will never be okay. How could you possibly think that they would be?

And what’s this about forgiveness? The voice went on. Fuck your foot and fuck forgiveness.

Fortunately, on Friday I had a phone call with my IFS consult group, led by the insightful Robyn Dickson. “Just acknowledge that’s what’s coming up for you is a part,” she said. “Sometimes just acknowledging that is enough, even if your system doesn’t believe it.” Again, the power of acknowledgement.

Robyn also reminded me that when you hear the voice of an inner critic, there is always a little one nearby who’s taking the criticism. “And get help,” she counseled. “Message your IFS friends. All you have to say is HELP! EXILE BLENDED.”

Robyn closed the call by sharing her definition of love, which is: “I trust your process.”

Those words echoed around my head after we ended our Zoom call. I tried to apply them to myself: Trust your own process. All the parts I had coming up that felt shame about being laid low, that thought that I should be beyond falling into despair, I thanked for their concern. I also welcomed my silver lining part, and her message: you are being shown what you need to heal.

That afternoon one of my IFS buddies answered my distress call. “You did this journey without the permission of your protector parts,” she said, “and it sounds like you’re having a backlash.”

I admitted that when I was tripping, I wasn’t aware of any of my parts at all. Instead, I felt pure presence and joy, as if I were nothing but Higher Self. (Okay, plus that sky smut part.)

“Well, your parts didn’t like being pushed aside,” she said, “This blanket of forgiveness was too broad a paintbrush, you did too much too quickly, and your protectors are like fuck that.”

After I got off the phone with her, I gave into the urges of my firefighters, who’d been raising their hands all day, and smoked some pot. I took a long shower. I changed outfits several times. I put on make up. Suddenly there was almost no time for the journaling reflection I’d been planning on doing after I got high. All I had five minutes and a blank page. What I got was:

Nothing will ever work out for you. You don’t deserve to be happy.

And then

You are a bad little girl who doesn’t make her mommy happy.

How old are you? I asked this protector.

Five, came the answer.

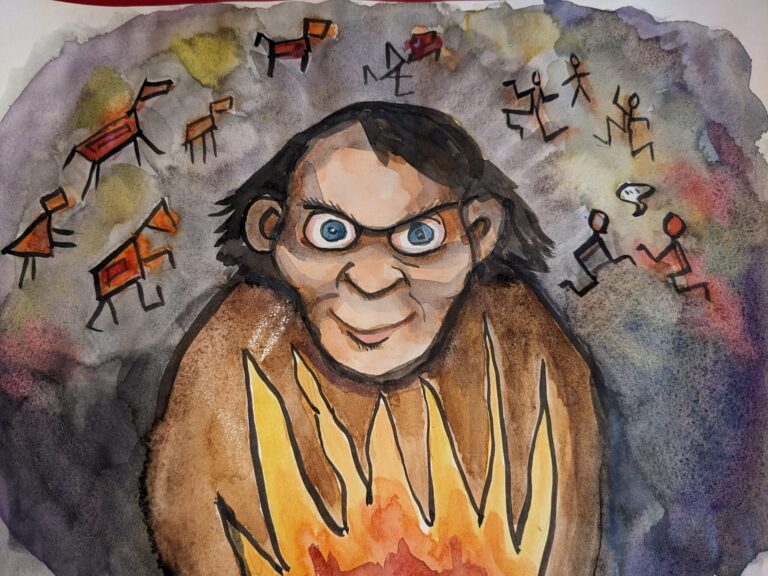

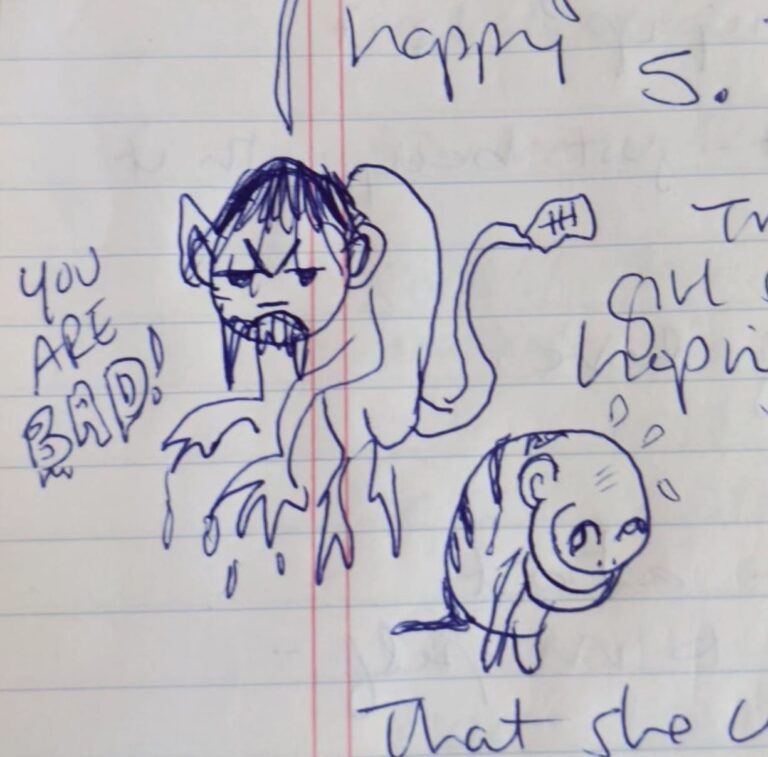

I sketched a five-year-old tormentor with fangs and talons bloodied from mauling a five-year-old victim.

My mother always called the summer I turned five “the summer that we fought.” I accepted this nomenclature, taking the blame and feeling like I must have been an especially contentious five-year-old. It took me years to recognize my childish behavior as a developmentally normal attempt at individuation—one that was systematically shot down with screaming, shaming, spanking and lots of getting sent to my room for “time out.”

While I can still remember details of the rental we lived in for one year (the chunky black and white TV in the living room, the cool concrete of the back porch, the front yard’s wisteria and dogwood), my room is a big fat blank in the middle of my memories. I can’t see the place where a part of me decided that if she was unloved she must be unlovable, and then set about keeping herself safe by shutting down any signs of hope or happiness. The parts of me stuck in the present tense of this lower-case t trauma were completely flipping out about the forgiveness message of my journey. These five-year-olds, monster girl and victim girl, were not ready to forgive.

My five-minute reflection over, I ran out the door to meet friends and have a few more drinks than my manager parts found prudent. Out and about with friends, I felt light and happy. At home again, the heaviness returned. I kept checking in with the little girl dyad. They came up as a welling in the throat, a tightness in the neck. They gave me more memories: the sky-blue Tar Heels sweatshirt I loved, going to the 7-11 where the drunk with toothpicks holding his eyes open made fun of it because we’d moved into garnet-and-black Gamecock territory. My mom said, “Don’t look at him,” but it was too late.

Moments of making art with my mom bubbled up. When I praised her ability to color within the lines and make smooth paper mache animals, she wouldn’t take my compliments. “I just have more eye-hand coordination because I’m older,” she said. “I’m not any good at art.” Her self-hatred hurt my heart.

We are not done, me and these parts. They have been asking to watch Mr. Rogers and listen to Free to Be You and Me. I have other parts that are super impatient, bored by the slow pacing of seventies educational TV, irritated by the didacticism of Marlo Thomas’ feminist monologues. More than anything these parts are yelling, let’s get rid of these girls so we can feel good again.

But I also know that this deep-seated duo that’s afraid to feel good is coming forth now because for the first time in my life, there is space for them. It’s not a “one and done” or overnight process. As my IFS mentors remind me, going slow is always faster. In the meantime, I keep visiting the monster and her victim, establishing a relationship with them, building trust.

To be continued…